Introduction

It is difficult to cover the history of Jain religion with in the scope of this book, but we will attempt to briefly out line the salient features.

Indian culture consists of two main trends: Shramanic and Brahmanic. The Vedic traditions come under the Brahmanic trend. The Shramanic trend covers the Jain, Buddhist, and similar other ascetic traditions. The Brahmanic schools accept the authority of the Vedas and Vedic literature. The Jains and Buddhists have their own canons and accept their authors.

Jainism is an ancient independent religion of India. However, it is wrong to say that Bhagawän Mahävir founded Jainism. Jainism is an eternal religion; it has always existed, it exists now, and it will always exist in the future. Jainism has been flourishing in India from times immemorial. In comparison with the small population of Jain, the achievements of their in enriching the various aspects of Indian culture are great.

Legendary Antiquity of Jainism

Jainism is an eternal religion. Therefore, there is a prehistoric time of Jainism and there is a historic time of Jainism. Jainism is revealed in every cyclic period of the universe, and this constitutes the prehistoric time of Jainism. In addition, there is a recorded history of Jainism since about 3000_3500 BC.

Prehistoric Period

According to Jain scriptures, there were infinite number of time cycles in the past (no beginning) and there will be more time ycles in future. Each time cycle is dividced into two equal half cycles, namely Utsarpini (ascending) Käl (time) and Avasarpini (descending) Käl. Each cycle is again divided into six divisions known as Äräs (spokes of a wheel). The Äräs of Avasarpini are reversed relative to those in Utsarpini. There are 24 Tirthankars in each half cycle. Kevalis known as Tirthankars teach religious philosophy through Sermons, which leads human beings across the ocean of sorrow and misery. Tirthankars are the personages who delineate the path of final liberation or emancipation of all living beings from succession of births and deaths.

The tradition of Tirthankars in the present age begins with Shri Rishabhadev, the first Tirthankar, and ends with Shri Mahävir swami, the twenty_fourth Tirthankar. Naturally, there is a continuous link among these twenty_four Tirthankars who flourished in different periods of history in India. It, therefore, means that the religion first preached by Shri Rishabhadev in the remote past was preached in succession by the remaining twenty_three Tirthankars for the benefit of living beings and revival of spirituality.

There is evidence that there were people who were worshipping Rishabhadev before Vedic period. It has been recorded that King Kharavela of Kalinga, in his second invasion of Magadha in 161 B.C., brought back treasures from Magadha and in these treasures there was the idol known as Agra_Jina, of the first Jina (Rishabhadev) which had been carried away from Kalinga three centuries earlier by King Nanda I. This means that in the fifth century B.C. Rishabhadev was worshipped and his idol was highly valued by his followers. Other archaeological evidences belonging to the Indus Valley Civilization of the Bronze Age in India also lend support to the antiquity of the Jain tradition and suggest the prevalence of the practice of the worship of Rishabhadev, the first Tirthankar, along with the worship of other deities. Many relics from the Indus Valley excavations suggest the prevalence of the Jain religion in that ancient period (3500 to 3000 B.C.).

It is observed that in the Indus Valley civilization, there is a great preponderance of pottery figures of female deities over those of male deities and the figures of male deities are shown naked.

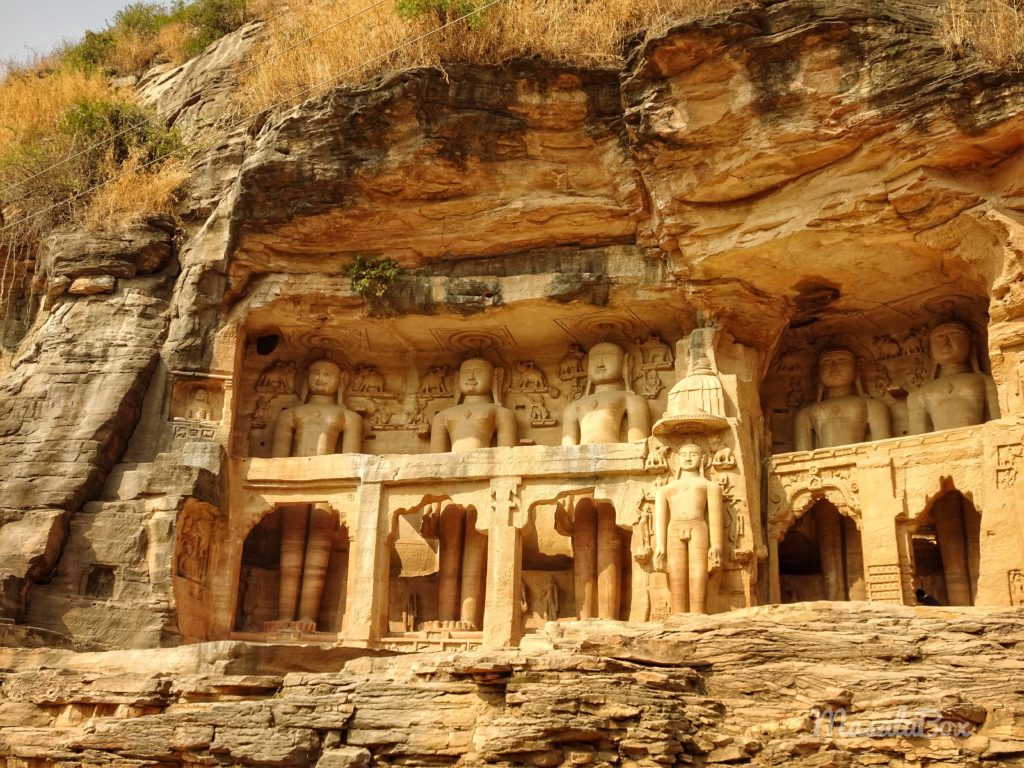

We find that the figures of six male deities in nude form are engraved on one seal and that each figure is shown naked and standing erect in a contemplative mood with both hands kept close to the body. Since this Käyotsarga (way of practicing penance, as in a standing posture) is peculiar only to the Jains and the figures are of naked ascetics, it can be postulated that these figures represent the Jain Tirthankars.

Again, the figures of male deities in contemplative mood and in sitting posture engraved on the seals are believed to resemble the figures of Jain Tirthankars, because these male deities are depicted as having one face only. While, the figures of male deities of Hindu tradition are generally depicted as having three faces or three eyes and with a trident or some type of weapon.

Furthermore, there are some motifs on the seals found in Mohen_Jo_Daro identical with those found in the ancient Jain art of Mathura.

As Mahävir was the last Tirthankar, most philosophers consider Mahävir_swämi as the founder of the Jain religion. Obviously, this is a misconception. Now, historians have accepted the fact that Mahävir_swämi did not found the Jain religion but he preached, revived and organized the religion, which was in existence from the past (Anädi Käl).

At present, we are in the fifth Ärä, Dusham, of the Avasarpini half cycle, of which nearly 2500 years have passed. The fifth Ärä began 3 years and 3 ½ months after the Nirvana of Bhagawän Mahävir in 527 B.C. Bhagawän Rishabhadev, the first Tirthankar, lived in the later part of the third Ärä, and the remaining twenty_three Tirthankars lived during the fourth Ärä.

Historical Period – Jain Tradition and Archaeological Evidence

Neminäth as a Historical Figure

Neminäth or Aristanemi, who preceded Bhagawän Pärshvanäth, was a cousin of Krishna. He was a son of Samudravijay and grandson of Andhakavrshi of Sauryapura. Krishna had negotiated the wedding of Neminäth with Räjimati, the daughter of Ugrasen of Dvärkä. Neminäth attained emancipation on the summit of Mount Raivata (Girnar).

There is a mention of Neminäth in several Vedic canonical books. The king named Nebuchadnazzar was living in the 10th century B. C. It indicates that even in the tenth century B.C. there was the worship of the temple of Neminäth. Thus, there seems to be little doubt about Neminäth as a historical figure but there is some difficulty in fixing his date.

Historicity of Pärshvanäth

The historicity of Bhagawän Pärshvanäth has been unanimously accepted. He preceded Bhagawän Mahävir by 25O years. He was the son of King Ashvasen and Queen Vämä of Väränasi. At the age of thirty, he renounced the world and became an ascetic. He practiced austerities for eighty_three days. On the eighty_fourth day, he obtained omniscience. Bhagawän Pärshvanäth preached his doctrines for seventy years. At the age of one hundred, he attained liberation on the summit of Mount Samet (Pärshvanäth Hills).

The four vows preached by Bhagawän Pärshvanäth are: not to kill, not to lie, not to steal, and not to have any possession. The vow of celibacy was implicitly included in the last vow. However, in the two hundred and fifty years that elapsed between the Nirvana of Pärshvanäth and the preaching of Bhagawän Mahävir, in light of the situation of that time, Bhagawän Mahävir added the fifth vow of celibacy to the existing four vows. There were followers of Bhagawän Pärshvanäth headed by Keshi Ganadhar at the time of Bhagawän Mahävir. It is a historical fact that Keshi Ganadhar and Ganadhar Gautam, chief disciple of Bhagawän Mahävir met and discussed the differences. After a satisfactory explanation by Ganadhar Gautam, Keshi Ganadhar, monks, and nuns of the Bhagawän Pärshvanäth tradition accepted the leadership of Bhagawän Mahävir and they were reinitiated. It should be noted that the monks and nuns who followed the tradition of Bhagawän Pärshvanäth were wearing clothes. (by shvetämbar tradition).

Bhagawän Mahävir

Bhagawän Mahävir was the twenty_fourth and the last Tirthankar. According to the tradition of the Shvetämbar Jains, the Nirvana of Bhagawän Mahävir took place 470 years before the beginning of the Vikram Era. The tradition of the Digambar Jains maintains that Bhagawän Mahävir attained Nirvana 605 years before the beginning of the Saka Era. By either mode of calculation, the date comes to 527 B.C. Since the Bhagawän attained emancipation at the age of 72, his birth must have been around 599 B.C. This makes Bhagawän Mahävir a slightly elder contemporary of Buddha who probably lived about 567_487 B.C.

Bhagawän Mahävir was the head of an excellent community of 14,000 monks, 36,000 nuns, 159,000 male lay votaries (Shrävaks) and 318,000 female lay votaries. (Shrävikäs). The four groups designated as monks, nuns, laymen, and laywomen constitute the four_fold order (Tirtha) of Jainism.

Of the eleven principal disciples (Ganadhars) of Bhagawän Mahävir, only two, Gautam Swämi and Sudharmä Swämi, survived him. After twenty years of Nirvana of Bhagawän Mahävir, Sudharmä Swämi also attained emancipation. He was the last of the eleven Ganadhars to attain Moksha. Jambu Swämi, the last omniscient, was his disciple. He attained salvation sixty_four years after the Nirvana of Bhagawän Mahävir.

There were both types of monks; Sachelaka (with clothes), and Achelak (without clothes), in the order of Bhagawän Mahävir. Both types of these groups were present together up to several centuries after Nirvana of Bhagawän Mahävir.

Jain Tradition and Buddhim

Bhagawän Mahävir was the senior contemporary of Gautam Buddha, the founder of Buddhism. In Buddhist books, Bhagawän Mahävir is always described as Niggantha Nätaputta (Nirgrantha Jnäta_putra), i.e., the naked ascetic of the Jnätru clan. Furthermore, in the Buddhist literature, Jainism is referred to as anncient religion. There are ample references in Buddhist books to the Jain naked ascetics, to the worship of Arhats in Jain Chaityas or temples, and to the Chaturyäma_dharma (i.e. fourfold religion) of the twenty_third Tirthankar Pärshvanäth.

Moreover, the Buddhist literature refers to the Jain tradition of Tirthankars and specifically mentions the names of Jain Tirthankars like Rishabhadev, Padmaprabha, Chandraprabha, Pushpadanta, Vimalnäth, Dharmanäth and Neminäth. The Buddhist book, Manorathapurani mentions the names of many householder men and women as followers of the Pärshvanäth tradition and among them is the name of Vappa, the uncle of Gautam Buddha. In fact, it is mentioned in the Buddhist literature that Gautam Buddha himself practiced penance according to the Jain way before he propounded his new religion.

Jain Tradition and Hinduism

The Jain tradition of 24 Tirthankars seems to have been accepted by the Hindus as well as the Buddhists as it has been described in their ancient scriptures. The Hindus, indeed, never disputed the fact that Jainism was revealed by Rishabhadev and placed his time almost at what they conceived to be the commencement of the world. They gave the same parentage (father Näbhiräyä and mother Marudevi) of Rishabhadev as the Jains do and they also agree that after the name of Rishabhadev’s eldest son, Bharat, this country is known as Bhärat_varsha.

In the Rig Veda, there are clear references to Rishabhadev, the first Tirthankar, and to Aristanemi, the twenty_second Tirthankar. The Yajur Veda also mentions the names of three Tirthankars, Rishabhadev, Ajitnäth, and Aristanemi. Further, the Atharva Veda specifically mentions the sect of Vratya means the observer of Vratas or vows as distinguished from the Hindus at those times. Similarly, in the Atharva Veda, the term Mahä Vratya occurs and it is postulated that this term refers to Rishabhadev, who could be considered as the great leader of the Vratyas.